In 2007, the nation’s housing bubble burst, leading to the Great Recession of 2008 and a rapid drop in property values across the country. While the recession officially ended in 2009, more than 9 million homeowners across the country still have mortgages on homes that are now worth less than they owe.

These underwater mortgages not only leave homeowners strapped for cash as they struggle with the residual effects of the recession and slow job growth, but can depress the value of nearby properties when those homes are foreclosed on, and hamper communities’ ability to recover from the economic crisis.

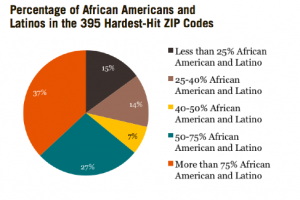

In the Alliance’s 2013 Wasted Wealth report, detailed the devastating impacts of the foreclosure crisis in communities of color. As a recent report by the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society similarly found, the communities of color have disproportionately high rates of underwater mortgages, compounding the existing wealth gap.

The federal government launched a number of efforts to help homeowners with underwater mortgages, but even with these efforts millions of underwater homeowners were left without help. In Florida, one of the 18 states included in the Hardest Hit Fund Principal Reduction Program, the initial call for applications lasted only a few days last fall before the cap of 25,000 applications was reached. The program has only helped 2,400 out of a goal of helping an estimated 10,000 homeowners. Florida plans to reopen the program to allow more homeowners to apply, but the pace to reach that goal of 10,000 is sluggish.

While another federal program, the Home Affordable Refinance Program (HARP), has helped over 3 million homeowners nationwide refinance their homes, the program only helps homeowners who have not missed a payment, who are employed or receive other income, and who have their loans served by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, severely limiting the number of homeowners eligible for the program.

With many homeowners ineligible for federal assistance programs, cities across the country are exploring options to help homeowners get their mortgages above water. However, state regulations and the big banking industry continue to fight these efforts.

When Richmond, Calif., wanted to use eminent domain to seize underwater mortgages, banks and loan servicers threatened to refuse to do business in the city, bringing lawsuits and pushing members of Congress to propose legislation to prohibit Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac from providing mortgages in cities that used eminent domain to seize mortgages.

Under the eminent domain plan, the city would have seized mortgages from banks, paying fair market value, then worked with a Community Development Financial Institution to reset those mortgages, based on the current fair market value.

When Seattle considered a similar use of eminent domain, leaders ran into another issue: state regulations limiting cities’ ability to use eminent domain. Limitations like these are designed to ensure that use of eminent domain is for a genuine public use and to keep cities from seizing private property without cause. In this case, however, the regulations prevented the city from using eminent domain to revitalize communities and keep residents in their homes.

Homeowners in cities like Seattle can’t wait much longer.

“Right now there are close to 70 active foreclosures in my neighborhood,” said Seattle resident Chetti McAffee. “I am one of the thousands of homeowners in my neighborhood who has had to fight the banks to save my home. I’m glad that the Seattle City Council has taken steps to address the issue; however, every day they wait to address the problem is another day where families’ lives will be ruined.”

So, how do cities and concerned citizens help homeowners with underwater mortgages? There may not be a one-size fits all solution, as Seattle found that what could potentially work in one state may be against existing regulations in another.

The Haas Institute report has a number of recommendations including:

- Voluntary principal reduction by banks and other loan holders;

- Purchase of underwater mortgages from banks and other loan holders by “publically-owned or nonprofit entities that are willing to restructure them with fair and affordable terms;”

- Using eminent domain both to seize mortgages in order to refinance and to seize vacant, foreclosed homes to convert them to affordable housing units;

- The purchase of foreclosed homes by publicly owned or nonprofit entities to convert them to affordable housing rather than selling them to speculators.

If eminent domain isn’t an option (as in Seattle), and the banks won’t budge, though, what is a city to do? John A. Powell , director of the Haas Institute, has a additional suggestion: work with “the financial community that owns these homes to agree on resetting these loans.”

With push-back against using eminent domain to seize mortgages, finding ways to entice banks and loan servicers to reset mortgages or sell them at market value may prove most successful in the long-term.

Just what does that look like? We’ll have more suggestions in the coming months as the Alliance works with the Reset Seattle coalition to find alternative solutions to help underwater homeowners and their communities, not only in Seattle, but across the nation.