Police violence is a national problem, and everybody has a stake in solving it

Another city has erupted in rage in response to a police killing.

After a week of peaceful protests following the death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore, “Charm City” was in flames. The authorities declared a state of emergency and deployed the National Guard.

In less than a year since the killing of Michael Brown by a Ferguson, Missouri police officer, numerous cases of police beatings, shootings, and killings of unarmed civilians — from New York to South Carolina, and from California to Baltimore — have grabbed the public’s attention.

Even white people like myself who identify with the “Black Lives Matter” slogan — the phrase that’s come to represent the movement against police violence — are stunned and emotionally drained by the almost daily reports of senseless killing and police brutality.

We’re tempted to turn away. But we can’t, because this issue is here to stay.

While we all condemn acts of violence, we must try to dig a little deeper to understand what’s happened in Baltimore and around the country. And we all have a responsibility to be a part of the solution — to channel this rage into real reform of the police.

Baltimore is wracked by pervasive poverty, racial segregation, and crime — a grim reality popularized for the rest of the country by the HBO drama The Wire. One in four families in the city live in poverty, nearly double the national rate.

Baltimore is also troubled by a long history of police misconduct and violence against its residents. According to The Baltimore Sun, the city has paid $5.7 million in settlementsfrom police-brutality cases since 2011.

That history helps explain the explosive reaction by a small number of people to Freddie Gray’s alleged murder by six cops charged in his death.

Gray died after having his spine severed while in police custody — without any clear reason for his arrest. Deaths like his are all too common. And police are almost never held accountable.

This time, however, the state of Maryland has leveled charges against the officers involved, ranging from false imprisonment to assault to second-degree murder. That prompted celebrations in Baltimore, but further clashes are all but certain without real reform.

What else can be done? A few things come to mind:

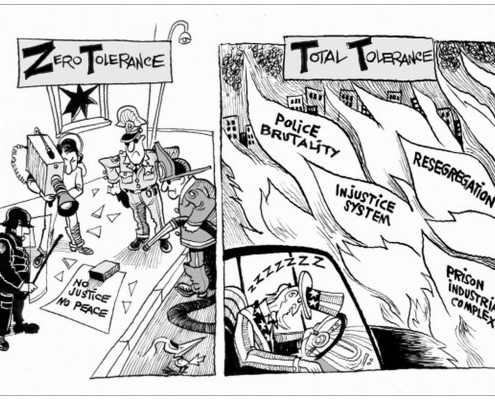

Racialized police practices like stop-and-frisk and “zero tolerance” policing must end in Baltimore and across the nation.

Cities should adopt alternatives to jails and prisons for nonviolent crimes. Programs like Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) in Seattle have proven effective in reducing recidivism by diverting low-level drug offenders to rehab instead of prison.

Other communities have found restorative justice effective, involving offenders in the process of repairing any harm they may have caused.

Most importantly, governments must follow the example set in Baltimore in the wake of Gray’s killing. All police officers must be held accountable for abuses such as beatings, killings, and corruption.

Many critics of Baltimore’s uprising have invoked Martin Luther King Jr.’s appeals to nonviolence. But don’t forget King’s other essential reminder: “A riot is the language of the unheard.”

The only way to show that our country has heard the anger and sorrow of black communities is to end impunity for police officers who commit acts of brutality. This isn’t a Baltimore problem or a Ferguson problem or a black problem.

It’s a national problem, and everyone has a stake in solving it.

Harsh policing and more prisons haven’t reduced crime or solved the problems of our communities. The only way to avoid another Baltimore is to overhaul standard police practices across the nation.